by Natalie Bennett

One of the great delights of living in London is that you can pop into the British Museum for an hour or so, make a couple of delightful little discoveries, then leave, without feeling that you have to consume the treasures in bulk.

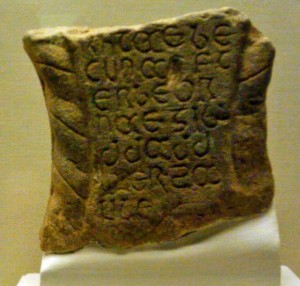

A subject that caught my attention today was Anglo-Saxon literacy, not a phrase that readily trips of the tongue. You might think of them as warriors, as farmers, as invaders, but not usually as writers. But I learnt that their runic script was called futhorc, and related to that of the Vikings. (Wikipedia says only 200 objects with it on have survived, so maybe my ignorance of the subject is not so surprising)

It is angular, being designed originally for incising on to hard surfaces such as bone, stone or wood, and most of these survivals consist of single words, like the name of the maker or owner, or short magical incantations.

As Christianity helped spread literacy, however, it was also used on manuscripts.

But the more flexible Latin script eventually supplanted it, and litreacy spread among the aristocracy and clergy. (Interestingly on display was a wooden writing tablet that would have been filled with wax, just like the many found at Vindolanda.)

One of the touching items on display is this part of a cross, in Old English written in Roman letters, from Yorkshire, reading “a monument in memory of his child, pray for his soul”.

There’s also a seax (knife) inscribed with the owner’s name – and I learnt that had I come from Essex I would have known this already, since its flag bears three of them.

The other item that caught my eye was this statue of sculptor Anne Damer.

Not because it is a particularly fine statue, not because the turning a female artist into a Madonna-like figure, whose works are her children, is reasonable, but because it is nice to see a woman from history highlighted.