To be offered the job of curating the new Islamic gallery at the Victoria & Albert Museum must have been akin to being offered the post of Home Secretary in a Blair government – an “exciting challenge”, but one full of potential disasters. Reading the gallery captions, you can almost see the writers tiptoeing through the religio-political minefield.

That’s not to say that the exhibition suffers for these modern realities. Simple, straightforward explanatory captions have a lot to recommend them, particularly given the current trend among some curators to try to draw big themes and grand narratives from simple, often everyday, objects.

Yet a huge, overarching theme does emerge, naturally, unforced, from this survey of 14 centuries of Islamic history. It is the pervasiveness of globalisation – not some 20th-century, Western-dominated phenomenon, but the ceaseless, restless interchange of ideas, images, and people between what we think of, too often, as the monoliths of “East” and “West”.

The exhibition begins with three simple stone capitals. While minor little barbarian princes might have thought of themselves as “Roman Emperors”, the real inheritors of the empire – much of its scholarship as well as much of its land, were the early Islamic rulers. From Spain, these capitals show 400 years of architectural development – not a sudden, abrupt, conqueror’s change, but a standard Roman capital that gradually acquires more complex, detailed decoration, while keeping its traditional shape, until 400 years later the Classical acanthus leaves have morphed into abstract shapes, their patterns decorated with Arabic script.

This extensive empire, just like its ancestral Roman state, was closely interlinked, as hinted by a spectacular bowl beside the stone testators. Made in Spain in the 15th-century, it is a spectacular, deep, metre-wide triumph of the potter’s art, featuring across its diameter a sailing ship. The anonymous artist has used the curves of the bowl to produce an astonishing sensation of movement.

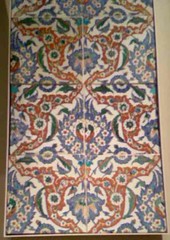

The flow of influences that might be broadly grouped as Chinese, Middle Eastern and “Western” are ever-present. The famous Iznik cermaics, developed under royal patronage in the 16th-century, owed their origins to Chinese imports, that inspired the initial blue and white ware to which technical innovators later added other colours. There’s an Ottoman silver-gilt ewer that had European-style dragons and fabulous beasts, and a shape like that of Western vessels of several centuries earlier.

The flow of influences that might be broadly grouped as Chinese, Middle Eastern and “Western” are ever-present. The famous Iznik cermaics, developed under royal patronage in the 16th-century, owed their origins to Chinese imports, that inspired the initial blue and white ware to which technical innovators later added other colours. There’s an Ottoman silver-gilt ewer that had European-style dragons and fabulous beasts, and a shape like that of Western vessels of several centuries earlier.

Just as today, however, there were casualties of this interchange. A beautiful 14th-century Syrian lustre jar of flying cranes is described as one of the last of its kind. The caption explains: “During the 14th century, lustre production became concentrated in Spain and large amounts of blue and white porcelain were shipped from China. Caught between the two, Syrian lustre production ceased.”

Lots of other simple verities of modern Westerner understandings of Islam are here overturned. “Islam doesn’t allow figurative art” – well you wouldn’t want to tell that to the 13th-century Syrian potter who made this delightful little ceramic ox, or the maker of the Iranian tile displayed above it that features a Chinese-style dragon. “Islam is resistant to science and learning” – well you wouldn’t want to tell that to the leatherworker, with all of his sharp instruments, who in 15th-century Egypt was working on the complex geometric patterns of a 1.2m-high bookcover whose intricate geometry wouldn’t allow for a single error.

Lots of other simple verities of modern Westerner understandings of Islam are here overturned. “Islam doesn’t allow figurative art” – well you wouldn’t want to tell that to the 13th-century Syrian potter who made this delightful little ceramic ox, or the maker of the Iranian tile displayed above it that features a Chinese-style dragon. “Islam is resistant to science and learning” – well you wouldn’t want to tell that to the leatherworker, with all of his sharp instruments, who in 15th-century Egypt was working on the complex geometric patterns of a 1.2m-high bookcover whose intricate geometry wouldn’t allow for a single error.

If one criticism might be made of this extensive collection of beautiful objects it is that there are few human, seductive stories attached to them. There is, however, one exception – four small, wonderfully elaborate kaftans. That’s a detail of one of them above. The curiously Seventies-style pattern and colours are the traditional Islamic take on a tiger’s stripes, and it was worn by a young boy – from its size of age six or seven. You can imagine him being proud of their colours, their symbolism, imagining growing up to hunt these great beasts.

He was not, however, to grow any older, for he was one of the 19 younger sons of Sultan Murat III, who were all executed at the succession of their half-brother Mehmet III in 1595, The four kaftans – none much bigger than this — on display here are thought to have survived because in line with Ottoman custom they were placed over those small, pathetic graves.

I’ve being walking around the edges of the gallery thus far, focusing on fascinating, relatively small objects that tell a very large tale. At the centre of the gallery is something different – a huge, spectacular object that simply cries out: “Wealth, Power.†It is known as the Ardabil carpet, “the world’s oldest dated carpet”. (The completion date — 1539 — is woven into its pattern, together with the name of the man who supervised its production, Maqsud Kashami.)

Most of the time when you walk into the gallery you’ll think, yes, big (10.5m by 5m), but what’s the fuss all about? For the lights over this overgrown mat are only switched on for 10 minutes on the hour and half-hour. When they are the astonishing brilliant colours – particularly the blue (which is echoed on the gallery walls) – emerge, and the sheer, detailed intensity of the pattern (4914 knots per 10 square cm, they say) is almost overwhelming.

Yet this is one of those grand, spectacular items that tugs the aesthetic sense but does less for the emotions. I think I’ll remember that little kaftan, and that spectacular ship bowl – genuine transports to another world, a world as changeable, multi-facted and exciting as our own.

Entry to the gallery (as with most of the museum) is free.

Other views: the BBc’s, the Observer explains the Ardabil carpet, the Iranian news agency’s report on the opening.

0 Comments

1 Pingback