Does it matter what your favourite novelist looks like? Well of course not, but it is human nature to be curious, and through the 20th century that curiosity was given full rein as writers went from being hidden figures in their garret to glamorous celebrities — or so at least their publishers hoped.

Between 1920 and 1960, women writers ruled the shelves of England’s bookshelves – at least in the popular market. “Being single, and having some money, and having the time – having no men, you see,” was how one of their number, Ivy Compton-Burnett, explained this trend. And it is these women — not all of them single — who dominate a new showcase display at the National Portrait Gallery.

Some are names that still resonate: Virginia Woolf, of course, Dorothy L. Sayers, Barbara Cartland, Daphne du Maurier and Doris Lessing. But others may test out the knowledge of even the most dedicated English graduate.

There’s Joanna Godden who wrote 31 novels, mostly about the farming communities and landscape of her native Sussex while also teaching and running a farm with her husband; she’s photographed looking terribly practical and matter-of-fact – the working writer at her desk. Then there’s the impressive Ethel Mannin, snapped in full avant-garde style with sleeked-down hair against a futuristic geometric backdrop. She wrote sympathetic accounts of the Soviet system in works such as Women and the Revolution and luxuriated, you get the feeling from the photo, in the title of “the most unpopular writer in Britain”.

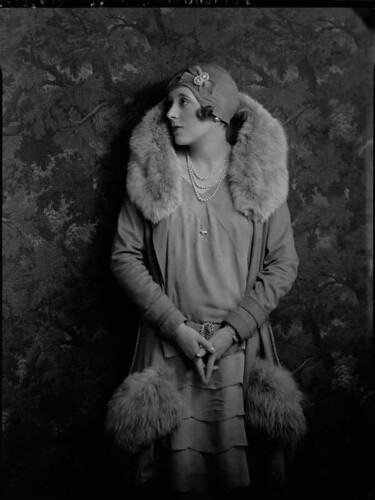

As photographic portraits, the 24 images can be broadly divided into two main groups – the glam and the homespun. A young Barbara Cartland photographed by Lafayette Ltd is a shock when we became so used to those self-parodying visions in pink toile and diamonds, is the very image of a young flapper. An image of Daphne du Maurier from c. 1923 has her looking terribly young and vulnerable – just waiting for the hero to sweep her off her feet.

Then there’s Angela Brazil. She was 36 when she started writing school novels so popular that they formed a genre all of their own, featuring schoolgirl slang, fervent friendships and respect for authority. Photographed at her desk, but with a scarf slung just so over her shoulder, she’s trying for a similar look that doesn’t quite come off.

A few of the women have the impossible cool look that just says pre-World War II aristocracy, however, no need for vulgar flashness.

Enid Bagnold, author of National Velvet is photographed in a studio with a couple of beautifully groomed children that surely must have been dressed by their nanny. Georgette Heyer, as you might expect from her novels, pulls off the same look, without the child accessories. And then there’s Nancy Mitford, photographed by Cecil Beaton about 1953. She looks just like you would expect, finished with pearls and perfectly swept-back hair.

Others went for a “family-friendly” look in more down-to-earth style. The young Doris Lessing was photographed very domestically in 1956 with cat. Enid Blyton went for the “children and dog on the terrace” look.

But some just look like the professionals they were. Noel Streatfield wrote the phenomenally popular Ballet Shoes, which drew on her own experience as a professional actor in the Twenties. But she allowed her imagination more rein in her adult fiction, particularly the successful Caroline England (1937) and The Winter is Past (1940), daring novels for their time that addressed illegitimacy, divorce, prostiution and homosexuality. There is, the viewer can imagine, a knowing, sad look in her eye, what you might expect from a young actress who’s seen a lot of the world.

For that’s what many of these women were – practical artisans. They earned their daily bread by reasonably pleasant, enjoyable work – but work it still definitely was. The popular romance writer Ruby Ayres said almost defiantly that she wrote for money. In 1955 she told the Daily Mail: “First I fix the price, then I fix the title, then I write the book” She could write up to 20,000 words a day. (I can do that in a week – and consider it pretty good going!) She’s pictured at her crowded desks with the additional note that she negotiated all her own contracts. And from this image, you’d believe it.

That “working woman” image was even stronger for Dodie Smith, the author of One Hundred and One Dalmnatians. She trained as an actress but ended up working in Heal’s furniture store, which still stands just up the road from the gallery. When her first play, Autumn Crocus was performed in 1929 it was billed as “shopgirl writes play”.

The display will continue until June 17 in Room 31. Free. Photographs courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery – copyright reserved.

December 18, 2006 at

Thank you very much Natalie. If I lived in London, I know where I’d go during this couple of weeks’ holiday I have.

Your descriptions bring out the reality of the women writers’ lives, the types of books women really wrote (to make money as well as to speak frankly), the distance from the way they posed and why they posed as they did.