By Natalie Bennett

The tradition of European painting started out small and intimate. Paintings were kept in cabinets, little more than book-sized, and brought out for intimates to share and admire. But around the 16th century that changed – they became larger, more items of general display to impress anyone who entered the room.

It was a change that didn’t happen in Indian painting, which remained small scale and usually on paper, maintaining a delicacy and intimacy lost in the larger European works. A new exhibition at the British Museum suggests what might have happened had European art stayed small, while also offering an insight into a tradition immediately, viscerally, foreign to our own.

The key difference is in realism, or the lack thereof. In Indian paintings psychological insight was regarded as more interesting than photographic reality – the aim is to convey information and elicit an emotional response, rather than accurately depict a single scene.

Having said all of that, the exhibition opens with its single large-scale work, an almost life-size image on paper of Maharana Karan Singh of Mewar (died 1628) painted a half-century after his death. Here we’re not far from the traditional European ruler portrait – all the symbols are there: imperial jewelry, weapons and sash, and he holds a flower just as Mughal emperors did in their portraits.

But after that the visitor familiar chiefly with European traditions is on unfamiliar ground, and will quickly learn new terms, and new ways of looking at paintings.

First up are paintings from the Punjab, north of the Ganges plain, belonging to the tradition known as Pahari, vibrant in colour and violent in emotion. In one the male lover listening anxiously to a female go-between, while in another room his beloved stretches langorously on the floor, leaning against a couch, straining in anticipation – there’s no doubt at all what she’s thinking about. But there’s nothing realist about the composition or style.

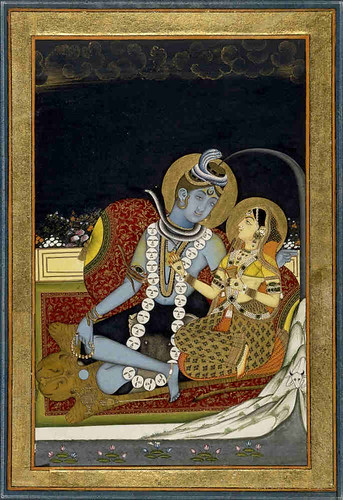

That’s a school of colour; next up is a school of weather and seasons — Barahmasa — paintings showing the seasons as they magnify the emotions of the characters within them. Storms of lovers’ emotions are obvious enough, perhaps cross-cultural, to our eyes cliched, but there’s a pleasing joy in the painting here of Diwali, showing Radha and Krishna playing a sociable game of chess on a terrace, while naked maiden frolic in a group in a lotus pond below.

Then there’s a school of music — Ragmala — paintings meant to be viewed in conjunction with certain types of music and at certain times of day, so evoking a particularly “rasa”, literally flavour, in 36 standard combinations. In one, Todi Ragini, a young woman is playing a veena while she waits for her lover. But he’s been so long that a deer and a peacock have emerged from the forest to listen. It’s clear, without words or overt symbols, that she’s growing sad, and fears he will never arrive – emotion-evoking indeed.

Those paintings all have a courtly feel, a studied, controlled sophistication meant, you can’t but feel, to be seen by only an elite few. It is the next small collection of Paithan paintings, from the central spine of southern India, that have the enthusiasm, dash and energy of a Blollywood movie. That’s fitting, since they depict the tradition from which the modern movie probably came – that of the market storyteller, who would use these works to illustrate key points in their long narratives.

I was particularly taken with a naive-styled, but extremely powerful and lively depiction of wild animals destroying the good king Harischandra’s millet fields. Blood drips cinematically from the neck of a gazelle as it is raked by the claws of a tiger, a cow meats a similar grisly fate at the teeth of a wolf nearby – it’s not hard to imagine the children, and maybe even the adults, drawn in by a skilled tale-teller, drawing back in horror from the scene.

All of these are proud traditions, clearly independent and free-acting, but somewhere, lurking in the back of the visitor’s mind must be the consciousness that on the historical horizon is the massive approaching impact of colonialism – that these traditions and their artists are soon to be hit by the great wave of British imperialism.

And it strikes here in the final section of this exhibition – in works described as of the Company school, commissioned usually by East India company officials from local artists, frequently within western tradition. And as you might expect from work done by artists struggling to come to terms with foreign domination there’s something stiff, fake, artificial about them. The tradition has been damaged — not fatally — but set back, warped, and will take some time to recover.

The exhibition continues at the British Museum until November 11 in room 91 (north of the Great Court). Entry is free. Other views: William Dalrymple in the Guardian, more about Indian painting styles.

Photos c. British Museum

Leave a Reply