by Natalie Bennett

The exhibition “Sleeping and Dreaming” at the Wellcome collection has much to delight the amateur scientist and collector of trivia. Did you know that lack of sleep changes your blood chemistry? That laudanum was invented by Paracelsus? That some of the first resuscitation devices – there’s one here from 1774 – involved tobacco being blown into the body via the rectum?

There’s also much to please the amateur psychologist. Did you know that roughly every second dream contains bizarre elements? That sexual dreams seem less common than is generally supposed? (Whatever is commonly supposed.) That women dream as often of men as women, but men dream more of men?

Yet this is also an art exhibition, from the traditional sculpture, “The Yawner” by Messerschidmt, part of a set of 100 heads showing all human emotions and moods, to distinctly modern work, such as Nils Klinger’s 2003

“The sleepers” photos – with an exposure as long as candle takes to burn down, so the movements of sombolence are mapped into one space.

It also has a strong political edge, provided particularly by the “Homeless Vehicle” designed by Krzysztof Wodiczko, a Polish-born artist in reaction to the estimate that in 1988 there were 70,000 homeless people in New York.

And there are the weird and wacky medical machines that are the items most usually associated with the Collection: my favourite was that invented by Friederike Hauffe (1801-1829), known as the “Seer of Prevorst”, one the best known somnambulists. It is a “nerve tuner” by which patients could be “magnetised”. An impressive collection of hanging flasks, odd wires – real mad inventor and gullible client stuff.

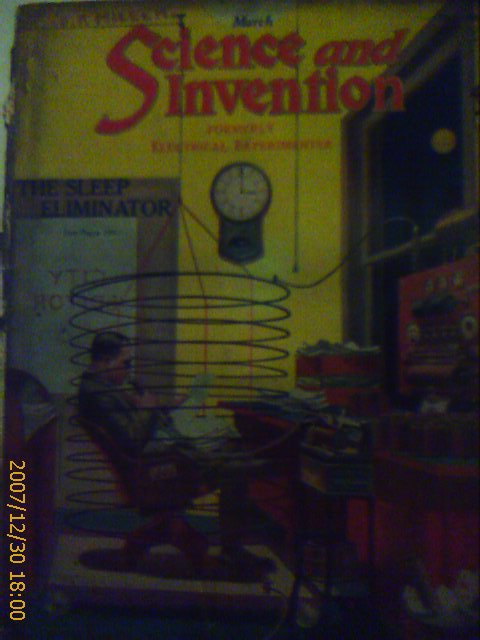

Although my favourite was the following, imaginary one, from Science and Invention, a popular sci-fi magazine in 1923. The cover illustrates a machine and inside the editor describes how sitting in midst of electric current and breathing oxygen would greatly reduce his need for sleep – and could get back to work at 3am without difficulty. (Would be very handy…)

Plus there’s proper science, such as the first sleep lab, built at the University of Chicago in 1925, where REM sleep was discovered in 1953. And images show how you can measure the consumption of glusoce within the brain (a measure of activity), with positron emission tomography.

But it is also clear how little we still know. The exhibition tells us: “Dreaming reinforces memories, it is thought.” And: “Do animals dream? It is likely.”

I’m a great believer in cross-disciplinary approaches to the world, and you don’t get any more varied in approach than this. But for all of the fascinating snippets, somehow this exhibition fails to make a completely satisfying whole. Perhaps its a question of the brain again – the frame required to appreciate a piece of art is jolted by the snippet of science. But perhaps, like an insomnia sufferer, it can be retrained – I’ll definitely be coming back to the next Wellcome exhibition to try again.

The exhibition continue at the Wellcome Collection until March 9. There’s also a permanent collection, a rather good cafe and an interesting little bookshop. Should you find yourself with an hour or so to kill at either King’s Cross or Euston stations, it is definitely worth the stroll.

January 7, 2008 at

Of all the shudder-inducing treatments dreamed up by doctors, the tobacco enema has to be right up there.

According to Jan Bondeson’s morbidly fascinating Buried Alive (New York, W.W. Norton, New York, 2002): “Antoine Louis [a surgeon at the Salpêtrière hospital in 18th century Paris] had also proposed another method of testing life, or at least stimulating the vital spark in the apparently dead person: with a powerful bellows, he administered an enema of tobacco smoke. One of the pipes of this remarkable apparatus was thrust into the anus of the apparently dead person; the other was connected, by way of a powerful bellows, to a large furnace full of tobacco. Such enemas of tobacco smoke were thought to be very beneficial and were used to try to revive not only people presumed dead but also drowned or unconscious individuals. In 1784, the Belgian physician P.J.B. Previnaire was given a prize by the Academy of Sciences in Brussels for a book on apparent death, which described and depicted an improved bellows for enemas of tobacco smoke, which he called Der Doppelbläser. These enemas were used well into the nineteenth century, particularly in Holland; modern science has discerned no physiological rationale to their use, except that the pain and indignity of having a blunt instrument violently thrust up one’s rear passage must have had some restorative effect” (pp138-40). Sadly, the author does not delve into the inspiration for the idea…Did the exhibition include an illustration of the procedure (Bondeson’s book helpfully does)?

Thank you for an entertaining and curiosity-whetting review – it makes me want to catch the next Eurostar across to view the exhibition!

February 8, 2009 at

My wife has a puppet (Chinese) that was mounted on the gateway at the 1923 Ideal Home Exhibition in London. I do know that the gateway was constructed for viewing by the Royal family at the time and was then destryoed except for a few pieces, which we have one of.

Do you have any other information or media covering the Ideal Home Exhibition of 1923?