“What do women WANT?” It is a classic question asked by an anti-feminist bloke, usually with a stagey layer of overlaid sarcasm, implying that half of the human race is unreasonable and impossible to satisfy. And if they are unhappy, it is neither this man’s fault, nor any other man’s.

The Women’s Library has the perfect answer, in its exhibition titled simply What Do Women Want?” Drawn entirely from its collections, covering a span of around 150 years, it comes to the conclusion that women over that time have wanted broadly the same things – access to decisionmaking in public and private spheres, safety, opportunity, respect …. and they’ve had to keep fighting for them, because they have often not been delivered until decades of campaigning, and even when delivered, they’ve been continually under threat.

As is usual with Women’s Library exhibitions, there is a strong interactive component, developed here through an innovative design. It looks a bit odd at first glance, but it grows on you. Each section of the exhibition has its own “tower”, from which accompanying artworks – created for it – are strung, while it also forms a desk where visitors are invited to write their comments. These contributions take up one whole wall of the exhibition, and as usual make likely reading.

Housework, and why it is still seen as a woman’s job, is the scene of one of the hottest debates. Comments range from a joyous “hurray, don’t do it”, to a despairing “because it is crap work”, to the sarcastic “because men don’t do it ‘properly’ … clever boys”.

There’s also an online component to the exhibition, where visitors can leave their own responses to questions on each of the themes:

A VOICE – What issue would or do you campaign for?

BEAUTY – What makes a woman beautiful?

EQUALITY – What would improve the world of work for women?

HOMELIFE – Why is house work still thought of as a woman’s job?

PLEASURE – What is your favourite pleasure activity?

SAFETY & SECURITY – How can the environment be made safer for women?

One of the visual highlights is a small collection of suffragette banners. The one that really grabbed me was the shorthand writers’ – not, you’d think, a traditionally radical group, but they’d found a slogan all of their own. The banner made in 1908, designed by Mary Lowndes says: “Shorthand writers: speed fight on”.  Nearby is the 2005 version, a T-shirt reading: “This is what a feminist looks like.” The vote is achieved; the voice still needs to fight to be heard.

Nearby is the 2005 version, a T-shirt reading: “This is what a feminist looks like.” The vote is achieved; the voice still needs to fight to be heard.

In the homelife section too, some of the exhibits demonstrate how far we’ve come. There’s the pathetic little pamphlet from 1956 Directory of Homes for Unmarried Mothers and their Children – a list of 38 across the whole country, and you can imagine how the women would have been treated. Nearby is a Spare Rib magazine from 1973. “Could one of these women lose custody of their child? Lesbian Women in Court.”

Yet other aspects of “homelife” are less promising. A handwritten letter from a teacher responding to a 1964 survey about combining full-time work and family life, says that this only possible if she is “willing to get up at 6am and go to bed late”. It has a nice parallel with one of the artworks, The Greatest Show on Earth created for the exhibition by HEBA women’s project. It is an upside down umbrella with a number of gloves emerging from it, juggling children, briefcases, shopping bags, and an evening bag.

Violence too, is an issue on which it seems little or no progress has been made. A poster from 1985 published by the National Association of Youth Clubs, showing a woman walking through a dark, almost derelict, subway. It reads: “All your parents tell you is ‘be careful’. But they don’t tell you of what. It’s no good telling an attacker ‘I’m being careful’ is it? I think the worst thing of rape is afterwards when everyone says things. A girl was raped. Every boy she went out with afterwards tried it on. They said come on, she must have led him on…” Nearby, from 2005, is a testing kit to determine if a drink has been spiked, and protective caps. The message hasn’t changed – as of course we were sadly reminded, twice, last week: Women are to blame for being victims of crime, so they are told.

The issue of “beauty” is, possibly, even more depressing. Appearance in the first half of the century seems to have been very much tied up with employment. A magazine suggesting training and careers for “business girls” stresses the importance of dressing like an American. Nearby is a wonderfully paternalistic leaflet from J. Lyons and Co of teashop fame, setting out the features of a perfect employee: ribbon “clean and pressed” (around the front of the pert little hat), hair “neat and tidy”, “all buttons sewn on with red cotton”, dress “correct length” (about mid-calf), “well-polished plain shoes, medium heels for comfort.” (Looking at the heels the model is wearing, don’t think I’d fancy being on my feet all day in them.)

The modern equivalents are less overtly patronising, but among them are the classic skeletal young model, and other images of “high” fashion. The aim seems to be a combination of sexual appeal and one-upwomanship; at least the early stuff had a professional purpose. (The exhibition quotes an EU survey saying that 93 per cent of British women use cosmetics in some form, the highest percentage in Europe, and a 2005 survey in Bliss magazine found only 8 per cent of young women were happy with their body.)

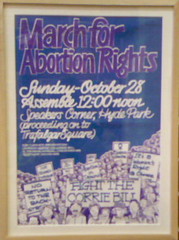

There’s also a salutary reminder that abortion rights can never be understood to be assured.  There’s a poster from 1979, when the MP John Corrie introduced a bill to restrict the right to abortion, a dozen years after the right had apparently been secured.

There’s a poster from 1979, when the MP John Corrie introduced a bill to restrict the right to abortion, a dozen years after the right had apparently been secured.

Overall, any woman who considers themselves a feminist is unlikely to learn a lot of new information from this exhibition, but it is both comforting and depressing, all at once, to think of our foremothers going through the same battles. And perhaps we should think about reading more of their history, and perhaps learning from their successes, and failures.

Leave a Reply